Hey folks. Happy summer!

Gosh, thinking about football in June is a lot. Unless you’re really into reading the OTA tea leaves--no shame if you are--this is the time to sit back and relax. Maybe catch some basketball if you’re into that sort of thing. If you follow me on Instagram--you should!--you may have figured out that I’m done with the NBA for the season. Another season, another disappointment for the Timberwolves. Oh well, life goes on

I know that I wrapped up my last post promising a more holistic look at the offseason. Don’t worry, that’s still in the works. But I’ve had a few things bugging me in the meantime, so I’m moving those up the list. Sue me.

Onto the things that bug me. Specifically, I’m going to be fleshing out some thoughts relating to a little Bluesky spat I got in the other day. (I guess I’m just begging for followers now, so feel free to get some of the worst takes imaginable here). If you’ve met me before (in real life, none of you parasocial sickos out there count (double parenthetical here, if you’re a paid subscriber you’re not a sicko you’re my best friend)), you may know that I have a bit of an argumentative streak. Heck, if you met me before my mid-20’s, it may be the only thing you remember about me. Nothing gets me motivated to do research like some viewpoints that challenge my priors.

In this case, there was a bit of a back-and-forth about the efficacy of tanking in the NFL. My prior is that tanking can work if executed correctly (I’m not a fan of the practice, but that’s for another day). But what does that sentence even mean? What is tanking? What does it mean for tanking to work?

Tanking

I think most sports fans have a general sense for what tanking is, and I don’t necessarily think that a precise definition adds too much value to the discourse. From a 30,000-foot view, tanking is the practice of intentionally--though potentially faux-surreptitiously-- losing a large number of games over the course of a season or multiple seasons in order to accrue premium draft picks by finishing at or near the bottom of the league. If you want a refresher on the relative value of draft picks, you can start here. For the purposes of this article, I’ll be defining tanking as knowingly taking one’s team out of short-term title-contention in service of long-term title-contention. You can call it “rebuilding” if it makes you feel any better.

For fans, this whole experience can suck. No one wants to root for losing. It was a bummer for Philadelphia 76ers fans during the Sam Hinkie era, it was a bummer for the Browns fans in the Sashi Brown era, it was a bummer for the Dolphins during the tank for Tua… it’s just a bummer.

But that doesn’t mean it doesn’t work.

There’s this belief out there among some fans that, if you’re running a football team, you simply must be concerned with creating a winning culture. You can’t condone tanking, because then you’re condoning a losing culture and you’ll turn into an organization with losing in its DNA. There’s probably some value to that thinking! But taken too far, it can be disastrous.

The issue with this idea is that it means that every team should, every season, try to get a little bit better that offseason, damn the future consequences. These people must wrestle with the Giants extending Daniel Jones and the Jaguars extending Blake Bortles; to move on from these almost-serviceable QBs would’ve been to take teams that made playoff runs (in Bortles’s case, to be a play or two away from the Super Bowl) and almost certainly take them out of the running in the next year. For reasonable people, these contracts were looked at as mistakes. But if you moved on from these QBs after their zeniths, the team would almost certainly be worse in the coming year. Does that yield a “losing culture”? Should every mediocre team, as soon as things break their way and they make the playoffs, sign all their veterans and go all-in with a pair of twos (that’s poker for “bad”)?

I mean, obviously no, but this is a data-forward publication, so let’s look at some data that agrees with me (to be clear here, I’m not cherry picking, the data just does agree with me).

Potential Biases

I said earlier that tanking can work if executed correctly. If you’re a regular reader of the Kelly Criterion, you may remember that I believe that impatient owners can be disastrous for constructing a winning team. If this were the case, it would mean that there are some organizations that are irrational actors and are more likely to be bad. That second part is important. If an organization is led by a bad owner with a lifetime tenure at the top, that organization is likely to be consistently bad regardless of whatever structural forces are supposed to force the league towards parity.

Among other things, this means that the cellar of the league is likely to be occupied by a bunch of losers incapable of doing anything right, including tanking. These teams are likely to be bad and stay bad not because of a losing culture, or because tanking does or doesn’t work, but because the decision makers are bad at their jobs and unlikely to take themselves out of decision making positions. This makes any analysis of tanking tricky; how do you separate the perennial losers from the savvy tankers? I’m not going to be correcting for this bias, just acknowledging it from the get-go; as you’ll see later on, there’s some powerful stuff even without correction.

Obviously, there is a flip side of this coin. If you think of team-building as a zero-sum thing, where every team’s wins are another team’s losses, then there must be a bunch of winners taking advantage of the losers. Again, not a bias that you need to correct for as a rule. It’s just worth mentioning that good and bad teams might stay good or bad not because of anything other than that they’re run by good and bad owners with good or bad front offices.

Team Transiency

With that out of the way, let’s get into some numbers. Thanks for sticking with me, let’s talk tanks.

To evaluate team strength in a given season I’ll be leaning on Pythagorean Win Expectation. This is an idea taken from baseball but applied across all sports, estimating the expected number of wins a team should have based on their points scored and the points scored against them.

It’s not a perfect metric for team strength, but then again nothing is and it’ll serve the purpose here. For every season, I’m taking the Pythagorean win expectations for every team and ranking the teams 1-32 (or less than 32 before the expansions). I’ll be labeling teams in the top 25% of a given season Great, the next 25% Good, the third 25% Okay, and the last group Bad.

The NFL didn’t have “real” free agency until the 1993 season, and didn’t implement the rookie wage scale until 2011, so I’ve split up my analysis by era: Before Free Agency, Before Rookie Wage Scale, and Modern NFL.

To start, let’s look at year-to-year transiency. What I’m technically giving below are some stacked Markov matrices, which show the probability of going from a given state (i.e. Good) to another state (i.e. Bad) in the following season.

You can read that as: A current Great NFL team will only be “Bad” in the following year about 5% of the time.

A few obvious points here. Basically forever, the best predictor of being a great team next year has been to be a great team this year. However, it has never meant less to be great than it does now, with the Great-Great relationship diminishing through the eras. Further, bad teams in general stay bad, and very very infrequently make the jump from bad to great in a single season.

In general, the extremes are a lot stickier than the middle. The outside 16 teams, bad or good, are a lot more likely to keep their place than the middle 16.

So I was wrong, tanking will never work because bad teams are bad, right? No. Keep on reading.

Minimum Future Rank

Obviously, looking at season-to-season transitions can be powerful, but it doesn’t tell the whole story. The fact that most bad teams don’t instantly ascend to become great teams in a single offseason is not a nail in the tanking coffin. What’s more interesting--to me, at least--is a look at how teams that finish the season at a certain Pythagorean Rank go on to perform in the coming years.

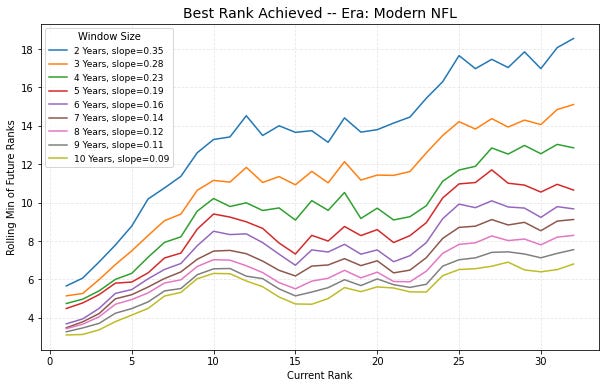

To answer this question I’ve taken the minimum rank that every team reaches in the N (for N between 2-10) years after a given season and compiled the averages, binning by starting rank. You can read these graphs as: if your team finished as the xth best team in the league, what is the best they’ll be over the next N years.

The first two graphs sort of vibe with what you might expect with no forces trying to induce parity - bad teams in a given year are unlikely to reach the same heights going forward as good teams in that same year.

So what changes in the modern era?

Looking at a four-year window, there is practically no difference between the expected peak ranking of a team who finished 10th in the league and 23rd. There’s a nifty mechanistic explanation for this, too; that team who finished tenth in Pythagorean wins is likely under pressure to keep up that prized “winning culture”, causing them to spend a bunch of assets they don’t have to try to catch up to teams out of their league.

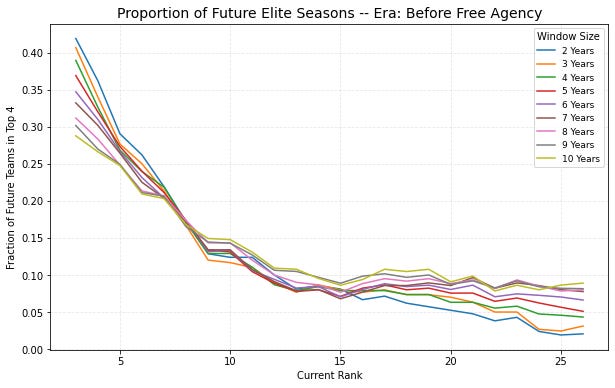

What if we look at things a different way? Let’s take the proportion of seasons a team finishes in the top 4 in the future--we’ll call that having a puncher’s chance at the title--based on their current rank.

Again, the first two eras tell a clean story and the modern era gets trickier. The way things currently play out, a team that finishes tenth in the league, over a four year window, is likely to field fewer elite teams than the team that finished 30th. How’s that for a “winning culture”?

I don’t make the rules, I just crunch the numbers and report what I see. There is no more dangerous place to be in the modern NFL than to be a team in the middle who thinks they’re a play or two away and decides to bet the farm on it.

I’ll leave y’all with this. In the final week of the 2020 season, finishing at the bottom of their division and with nothing to play for but a draft pick, the Eagles benched their starters, intentionally lost the game, and drew the ire of their own players. Jason Kelce was pissed, the “winning culture” was gone, and you had think pieces like this being written. Take this quote:

“The Eagles' brass deserve every ounce of disillusionment they'll sense inside their locker room at the end of this year and the start of the next. Every little bit of resentment for the draft pick that was important enough to put their bodies on the line for. Best of luck to them pacifying a hive of pissed off veterans and their expensive former starting quarterback, who is also reportedly trying to muscle his way out of town. Whichever person orchestrated this ludicrous display (and it’s fair to wonder, given Doug Pederson’s job security, who above him on the chain signed off on this plan) should have to personally explain it to Jason Kelce’s face afterward, just two weeks after he stressed the importance of winning over everything regardless of circumstance.”

Wow. With a narrative like that, you think it’d be impossible for Philly to do anything in the years after 2020. Could you imagine a team that lost the locker room, lost its culture, and intentionally tanked going on to make the playoffs four straight seasons, go to two Super Bowls, and win one?

Everyone I argue with online is this exact person. Again, I do not make the rules.

Obviously none of this work is possible without public support. Kindly consider donating here or, better yet, becoming a paid subscriber.

Some things I think I think

Why did the Miami Dolphins Logo Ditch the Helmet?

This is not news, but it did come up in bar trivia for me this week. That sucker was so cool, and now it’s way too slick. What did they take away from us?

With sports as entertainment, incentives matter.

I thought a lot about “foul baiting” in basketball last month (who can guess why). If you buy that it exists, it’s sort of a problem for the sport. At a first approximation, players are incentivized to get the ball in the basket in basketball (duh). This is cool and fun to watch.

Then you start to realize you should be taking the shots that generate the most expected value (which means that you opt for more 3-pt shots). This is still pretty cool and pretty fun to watch.

Then you start to realize that, to win games, you are incentivized to run plays that generate the most points. Almost any competent free throw shooter is more efficient at the line than he is shooting a contested shot from nearly anywhere on the court. Incentives drive action. This is less cool and less fun to watch.

If you don’t want free throw baiting, change the incentive structure. If you don’t want teams fouling up 3, change the incentive structure. If you don’t want teams to tank, change the incentive structure.

I’ve got a lot more thoughts about this, but I actually have the skeleton of a post written in my head about tanking alternatives, so I’ll leave it there for now.

Elden Ring Nightreign is so close to being so good

Iykyk. I feel like with a little bit of developer support this game is going to be rocking. One man’s opinion. Thought hard about deleting this section, but it was a thing that I think.